In the quiet corridors of the National Archives in Kew, thousands of miles from the heat and dust of Harare, a ghost has been stirred. Newly declassified British government reports have laid bare a secret that many in the high offices of Munhumutapa Building have long suspected: that at the height of our nation’s economic turmoil in the early 2000s, the United Kingdom seriously weighed the possibility of a military overthrow of the late Robert Gabriel Mugabe.

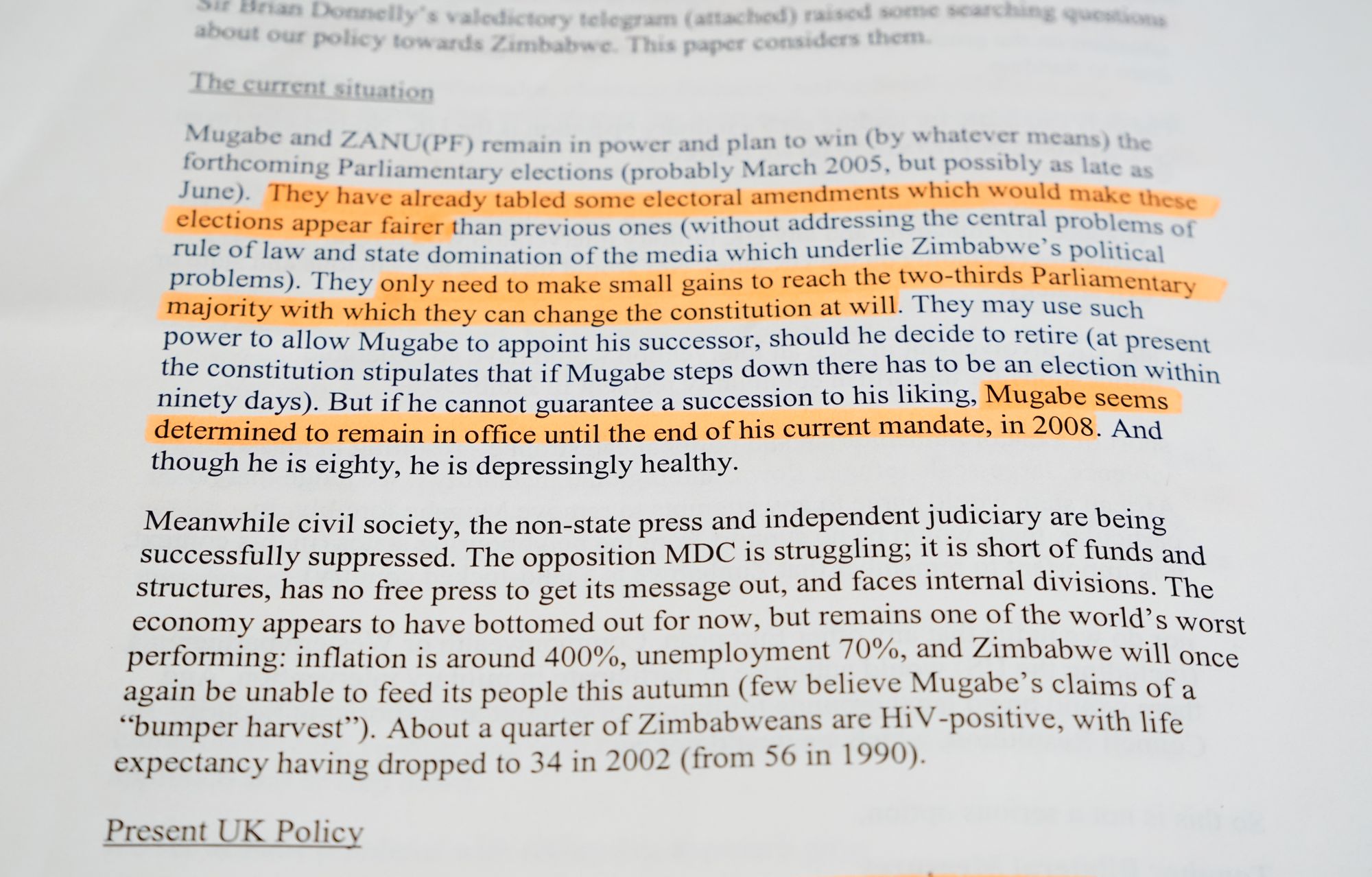

The documents, released this week, reveal a British establishment gripped by a mixture of desperation and “mounting frustration” as they watched the man they once knighted transform into their most formidable antagonist. At the heart of these deliberations was a startlingly blunt assessment of the veteran leader’s vitality. While the West waited for nature to take its course, Foreign Office officials were forced to admit that the then 80-year-old Mugabe remained “depressingly healthy” and showed no signs of loosening his grip on power.

The Military Option: A Non-Starter?

The year was 2004. The UK was still reeling from the fallout of the invasion of Iraq, a factor that heavily weighed on the minds of Tony Blair’s advisers. An options paper drawn up in July of that year was quick to throw cold water on any dreams of a “regime change” operation in Zimbabwe.

“The only candidate for leading such a military option is the UK. No one else (even the US) would be prepared to do so,” the declassified paper stated. The risks were deemed too high, with officials warning that “any UK military intervention would result in heavy casualties (including on the UK side).” Furthermore, the British feared they would find themselves in a quagmire with no “obvious end state or exit strategy.”

Perhaps most tellingly, the British recognized that they would find no friends on the African continent for such an adventure. The report judged that “no African state would agree to any attempts to remove Mugabe forcibly,” unless there was a “major humanitarian and political catastrophe.”

These revelations lend weight to claims made years later by former South African President Thabo Mbeki. Mbeki famously alleged that Tony Blair had tried to pressure him into joining a military coalition to topple Mugabe. While Blair has always “strongly denied” the claim, these files show that the suggestion was indeed circulating within the British government’s inner circles.

The “Gaddafi Model” and the Big Lie

As military force was ruled out, the British looked for other ways to “steel themselves” for the Mugabe problem. Sir Brian Donnelly, the outgoing British ambassador at the time, suggested a radical shift: engagement. He pointed to the success Blair had in bringing Libya’s Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in from the cold.

“I can well understand why you and the prime minister might shudder at the thought given all that Mugabe has said and done,” Donnelly wrote in a telegram to Sir Nigel Sheinwald, Blair’s foreign policy adviser. “I also recognise Mugabe’s unique place in our demonology creates some special problems with UK public and parliamentary opinion. It is a political call. All I can say is that you steeled yourself to do it with Gaddafi, another megalomaniac, often irrational de facto dictator. The payoff more than justified the effort.”

Blair seemed intrigued, noting that the UK should “work out a way of exposing the lies and malpractice of Zanu-PF up to the election and then afterwards, we could try to re-engage on the basis of a clear understanding of what that means.”

However, the Foreign Office remained sceptical. They feared that new sanctions would only hurt ordinary Zimbabweans and provide Mugabe with more ammunition for his “big lie”—the narrative that the UK was the sole architect of Zimbabwe’s economic woes. The conclusion at the time was a weary one: the UK would have to “hang firm” until Mugabe chose to go of his own accord.

The 2017 Finale: A Different Kind of Intervention

It would take another thirteen years for that “accord” to be reached, and when it happened, it wasn’t a British paratrooper who led the way, but Zimbabwe’s own military. The events of November 2017, which saw Mugabe finally deposed, were a masterclass in political theatre and international shadow-boxing.

The international community’s fingerprints were everywhere. The United States, despite its public stance of “wait and see,” appeared to have a clear view of the coming storm. On November 14, 2017—a full day before the military officially announced its intervention—the US Embassy in Harare issued a stern warning to its citizens. They were told in no uncertain terms to avoid the Harare Central Business District (CBD) and to “shelter in place.”

This early warning has long fueled speculation that Washington knew exactly what was about to happen. Yet, they took no steps to save the man who had once been the darling of the West. The silence from the White House was a clear signal: Mugabe was on his own.

The Dragon in the Room

Perhaps the most significant international player in Mugabe’s final days was China. For years, Mugabe had touted his “Look East” policy as the antidote to Western sanctions. But in the end, the Dragon also turned.

Just days before the military moved, General Constantino Chiwenga, the commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, was in Beijing. While the Chinese Foreign Ministry described it as a “normal military exchange,” the timing was anything but normal. Insiders have long maintained that the Chinese government backed the military generals, preferring the more “business-friendly” Emmerson Mnangagwa over the increasingly erratic Mugabe and his wife, Grace.

Reports suggest that the Chinese provided the generals with “promised backup” should the situation spiral out of control. Beijing wanted stability for its massive investments in Zimbabwe’s tobacco, diamond, and infrastructure sectors, and they saw Mugabe as a barrier to that stability.

The Legacy of a “Megalomanic”

As we look back at these declassified reports and the eventual fall of the “Grand Old Man” of African politics, the irony is thick. The British, who once “shuddered” at the thought of engaging him, watched from the sidelines as his own “all-weather friends” and his own soldiers did what London could not.

Rod Pullen, Sir Brian Donnelly’s successor, once wrote of Mugabe: “He is not mad (as some suggest), nor is he simply clinging to power out of fear (as others suggest). Rather he comes across as believing he has business to finish.”

That business was eventually finished in the cold light of a November morning in 2017. The declassified files remind us that while the world’s powers may plot and plan in their archives, the final chapter of Zimbabwe’s history is always written on the streets of Harare—sometimes with a nudge from the East, a warning from the West, and a constitutional script from the former colonial master.

Mugabe is gone, but the lessons of his long reign and the international intrigues that surrounded it remain as relevant as ever. In the end, the “depressingly healthy” leader was outlived not by his enemies’ plots, but by the very system he helped create.

Follow @MyZimbabweNews